As the lights went up for intermission I turned to get a good look at my people. People with whom I clearly share a bona fide kinship. Modern, connected America being all about sub-sets of sub-sets of smaller and tighter cults of like-thinkers, “these people”, I thought, “must be mine.” Who else would tuck into a theater on the hottest afternoon of summer to see a 50 year-old movie most likely for the umpteenth time.

As the lights went up for intermission I turned to get a good look at my people. People with whom I clearly share a bona fide kinship. Modern, connected America being all about sub-sets of sub-sets of smaller and tighter cults of like-thinkers, “these people”, I thought, “must be mine.” Who else would tuck into a theater on the hottest afternoon of summer to see a 50 year-old movie most likely for the umpteenth time.

Heading toward the lobby I found myself following a very tall, very large blonde woman. Open-toed pumps with two-inch heels, a light summery white dress with dainty floral patterned trim, a small white hand bag held delicately by the handle and a tight, prim page-boy hair cut. But tall. And large. Easily 6′ 2″ and, um, not obese, but definitely large-boned.

As I considered going over and asking her how many times she’d seen “2001: A Space Odyssey”, or if this was a first, since it was in town (at the Emagine Willow Creek, now held over a second week) in 90% of its original splendor — 70 mm film, with immaculately preserved color and definition, but not in Cinerama — she turned toward me. And despite the carefully applied lipstick and eye shadow, revealed just the barest hint of a 3 o’clock shadow. That and an Adam’s apple.

A fellow Stanley Kubrick geek, of the prim, put together and seasonally appropriate trans variety. You know, my people.

I’m a little sheepish about saying out loud how many times I’ve seen “2001”. But, what the hell, in theaters alone we’re closing in on 60. That’s um, let’s see … carry the three … roughly 150 hours of my life or nearly an entire week.

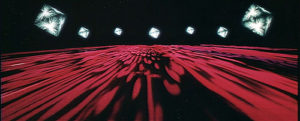

While there was once a phase of just going, usually in a moderately-to-highly enhanced state, to be pulled along on “the ultimate trip”, the constant overriding appeal has always been the admiration — the pleasurable sensation — of the film’s beauty, which is directly connected to an appreciation of the craft that made it.. It’s beautiful because it is so well made, and being so beautifully composed makes it beautiful.

“2001`” was consciously designed as a thing of beauty, with Kubrick describing it in terms of a symphony of cinema. (You can argue a great symphony elicits emotion and intellectual response with the command of only one sense, sound. While film, “2001” in particular, interweaves sound with image and all the photo-chemical balances available to the medium.)

And far from diminishing, the beauty of the movie — its concept, imagination, technical invention and audacity (three and a half years in production with $10.5 million of a publicly-traded studio’s money — $80 million today) — is as vivid as when it was released (to scathing reviews) in 1968. What’s more, “2001” remains today genuinely unparalleled, without valid comparison, certainly by any other mere “sci-fi” movie.

Not that I didn’t watch it — okay, twice last week — and imagine what The Maestro might do with it today if he had a chance to apply digital fixes to the few things beyond his control in the mid-Sixties.

Kubrick’s stated goal was a completely realistic sense of being in space, as best anyone could imagine it years before any human left low-earth orbit. The cliche movie word today is “immersive”, which I assume Kubrick would have accepted, considering his decision to shoot it for projection on gigantic curving Cinerama screens. (RIP Cooper Theater.)

The print being shown at Willow Creek is nearly perfect in terms of original color balance. Beautiful subtleties of color — ambers, ochres and muted yellows — in the African landscape in “The Dawn of Man” sequence are again visible after decades of being lost in washed-out, scratched-up 35 mm prints.

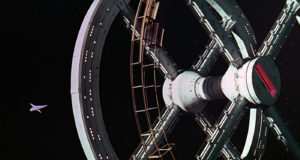

Tiny figures moving about the space station as the PanAm shuttle lines up for docking, and in the moon base Clavius as the bulbous Aries transporter is lowered, like a head on a platter, into the vast underground hangar are now clearly articulated.

Tiny figures moving about the space station as the PanAm shuttle lines up for docking, and in the moon base Clavius as the bulbous Aries transporter is lowered, like a head on a platter, into the vast underground hangar are now clearly articulated.

Everywhere the nearly pristine quality of the print restores the remarkable depth Kubrick always sought with his use of wide-angle, deep-focus lenses, especially in interior scenes.

As it is, the effect is very close to 3-D, which I strongly suspect would have been an option had the technology been (a lot) better than the cheesy junk it was in 1965-68.

At this point, Kubrick and “2001” are held in pretty much the same regard as Van Gogh and “The Starry Night”. Imitations are rampant but no one would ever consider “touching up” the original canvas itself.

But … if someone, like Christopher “Inception” Nolan or James “Avatar” Cameron were to take on a digital-reconstruction of “2001”, as, you know, a student’s homage to the master, an “unauthorized enhancement” of “2001” as Stanley Kubrick himself very, very likely would have preferred, based on everything we know about what he was going for, it would be a service to cinematic posterity.

For example, Kubrick would certainly be open to color-correcting for the “Dawn of Man” sequences where it is too obvious that the foreground action is taking place on a sound stage. The stage was lit as though in shadow from surrounding rocks, with the Namibian landscapes behind projected through the actors in their ape costumes. There’s a digital fix for that.

More glaring, in both the opening “Blue Danube” sequence and at the end when the Star Child floats back from his transmogrification, is the indiscernible white-ish blue blob that is meant to be planet Earth.

Actual film footage of the planet at that distance — maybe 20,000 miles out — wasn’t available in the mid-Sixties. But compare Earth as we see it in “2001” to what director Alfonso Cuaron and cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki did in “Gravity”, with the resource of countless hours of HiDef imagery available to them. Instead of an indistinguishable over-exposed celestial object, “Gravity’s” audience can easily see the shape of specific land masses, the lights of cities and coastlines. Apply the impact of that realism — especially as the Star Child contemplates what to do with his beautiful home and it’s ill-evolved inhabitants — and it’s unimaginable that Kubrick wouldn’t say, “[Bleep] yeah, that’s the shot I want!”

A digital fix could be applied there quite easily.

The biggest fix, certainly in terms of “immersiveness” and realism would be a big up-date in the soundtrack. The print at Willow Creek (supervised by Nolan), booms with the crispness of old, but there’s still only so much separation you can get with the limited digitizing they did off the celluloid film’s sound track.

Somehow there’s a way to toy with that, enhancing for example the threatening growl of the leopard in “The Dawn of Man” sequences, terrifying the man-apes huddled in their dried river bed, by pushing the roar out of speakers in the far reaches of the theater, a la Dolby Atmos. Likewise, “immersiveness” would be well served with more sound separation in the interior scenes, especially in the space vehicles with their subtle symphony of beeps and bleeps and burps.

Other than that, amazingly, there’s very little else the film more “contemporary”.

I was entertaining some of this as I returned to my seat after intermission. I lost track of the large, prim, trans blonde. But my attention was drawn to another of my people, a ringer for Jeff Dowd, the inspiration for Jeff Bridges’ “Dude” in “The Big Lebowski”. Maybe 60, wearing a loud Hawaiian shirt with long frazzled hair, the poor guy had obviously lost track of where he had been sitting. Wandering back and forth, finally some friend spotted him and yelled out.

The guy’s head snapped up. He raised a fist.

“Stanley!” he shouted. “The man!.”

Despite everything you see and hear and read (including here), somethings are evolving … in a good way. As a lifelong movie fan I’m encouraged — for different reasons — by what I’ve seen in two films now playing in a theater near you.

Despite everything you see and hear and read (including here), somethings are evolving … in a good way. As a lifelong movie fan I’m encouraged — for different reasons — by what I’ve seen in two films now playing in a theater near you.