I can’t see into the heads and hearts of KSTP-TV reporter Jay Koll’s and his editors, so I can’t tell you if their Pointergate story was racially, commercially or politically motivated.

I can’t see into the heads and hearts of KSTP-TV reporter Jay Koll’s and his editors, so I can’t tell you if their Pointergate story was racially, commercially or politically motivated.

When a reporter at a station owned by a large political donor immediately jumps to the unlikely conclusion that a black man and a politician pointing at each other is evidence of the politician’s support of criminal gangs, these are certainly fair questions to raise. But based on my dealings with reporters and editors over the last thirty years, I’d guess that the airing of the Pointergate story probably had a little to do with the biases that we all can fall prey to, and a little to do with what I like to call the Newsroom’s First Rule of Motion.

The Newsroom’s First Rule of Motion, is a cousin of Newton’s First Rule of Motion, which states that an object in motion tends to stay in motion. That is, once a reporter puts a story in motion — interviewing a source, getting editorial approval to pursue the story, making a few calls, Googling a bit, and gathering video tape — the story will almost certainly be aired, even if it begins to reveal itself as lightly substantiated, unsubstantiated or demonstrably false.

It’s simple inertia. Stories in motion tend to stay in motion.

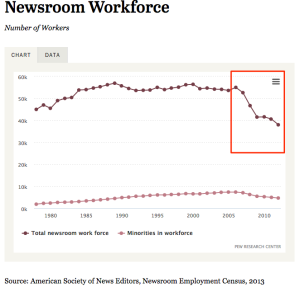

The Newsroom’s First Rule of Motion has always been a force, but it has become much more of a force since news organizations starting losing lots of money, and newsrooms consequently started getting much smaller. These days, if a reporter invests time in a story, and the story turns out to be lame, sparsely populated newsrooms have fewer stories in their pipeline to fill the news hole. Resource-wise, there is very little ability for unsubstantiated stories to die natural deaths.

The Newsroom’s First Rule of Motion has always been a force, but it has become much more of a force since news organizations starting losing lots of money, and newsrooms consequently started getting much smaller. These days, if a reporter invests time in a story, and the story turns out to be lame, sparsely populated newsrooms have fewer stories in their pipeline to fill the news hole. Resource-wise, there is very little ability for unsubstantiated stories to die natural deaths.

Because of this, the small group of remaining editors are less likely to seriously question or kill a weak or false story. Instead, they rationalize: “Well, we called the accused, so we’ll let viewers decide.”

As a result of this lack of responsible editing, we are treated to Mayor Hodges being forced to explain why pointing at someone is not ipso facto evidence of being pro-gangsta.

How do I know editors have become less likely to kill flawed stories? I don’t have research, just observations. I work in media relations, which occasionally calls for me to plead a client’s case to editors. Years ago, editors as a group were much more likely to give clients a fair hearing, and occasionally conclude that a demonstrably lame or false story should not run. Today, that almost never happens.

I have to believe that that is partly because financially stressed businesses can’t afford to have scarce hours, days or weeks of reporter time go for naught. Like everyone employed by for-profit ventures, reporters and editors have productivity pressures.

Of course, there are other types of problems associated with lightly populated newsrooms. With weaker newsrooms, it’s easier for scoundrels to get away with evil-doing, because there aren’t as many reporters available to put in the substantial amount of time and shoe leather that is often required to uncover evil-doing.

Whether because they are airing stories that should never air or missing stories that should be aired, smaller newsrooms make for less truth and light in our communities.

To be clear, I’m not saying Mr. Kolls and his editor should get a free pass for the Pointergate fiasco. Whatever the actual reasons that the story aired, it is a preposterous story with ugly ramifications. But I am saying that in addition to worrying about the bias issues associated with this specific story, we also should be worried about the lack of newsroom checks to prevent future unsubstantiated stories from airing.

– Loveland