I don’t want to belabor the similarities between Tom Wolfe and Nick Coleman, but since they’ve both passed within the same moment there are a couple qualities worth offering up for inspection.

I don’t want to belabor the similarities between Tom Wolfe and Nick Coleman, but since they’ve both passed within the same moment there are a couple qualities worth offering up for inspection.

There’s no question Wolfe and Coleman shared a distaste often bordering on contempt for meek and restrained conventional journalism. The world was more vibrant and nuanced and, hell, theatrical than what your average daily broad sheet was describing to you.

They also shared a level of self-confidence that egged them on to conflicts with peers and cultural figures they regarded as too immune to fair comment. A good, righteous battle required an adversary of substance.

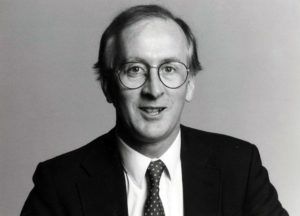

Nick was a friend I met back in the early Eighties when he was still the TV critic for the Tribune. I had been reading him faithfully for sometime before our mutual friend David Carr got us together, most likely for drinks, most likely at Moby Dick’s or some other unsanitized dungeon Carr was patronizing at the time.

Unlike every other TV critic I read as I kicked around the country, Coleman was scabrously funny. He didn’t see his role as a stenographic PR desk for the “stars”, be they Hollywood sitcom starlets or local TV anchors. His job description said “critic” and he flashed that license with relish.

Unlike every other TV critic I read as I kicked around the country, Coleman was scabrously funny. He didn’t see his role as a stenographic PR desk for the “stars”, be they Hollywood sitcom starlets or local TV anchors. His job description said “critic” and he flashed that license with relish.

I know it earned him a red circle around his name with the Hollywood PR machine. Nick Coleman: Not a reliable asset, if you know what I mean. (Long after he left the beat former colleagues around the country were telling hilarious stories of Coleman, in big ballroom interview sessions, commandeering the mic and gleefully vivisecting some pompous network executive or creative wunderkind du jour.)

He and I grew closer in the two years Carr, Eric Eskola and I produced a weekly half hour media talk show, “The Facts As We Know Them”, on cable access. Coleman was a regular guest, and as you’d expect from a guy whose father was a prominent politician, the most dangerous place in the studio was between Nick and the camera.

But we kept asking him back because, A: Preening for the camera was what we were all doing, B: Coleman could tell a damn good story and therefore hold the room, and C: His factuality was way better than average, even allowing for plenty of righteous hyperbole.

Like Wolfe, Nick was genetically coded for center stage. That fact of character may well have been to key to his undoing as time passed and newspaper managers became steadily less comfortable with big, in-your-face personalities with lots of thoughts on every imaginable topic.

The guy had a very unique career path. As dyed-in-the-green Kerry wool a son-of-St. Paul as you’ll ever find, Nick leveraged his popularity (among readers, if not editors and disapproving, convention-bound newsroom colleagues) over to the Pioneer Press and then back to the Strib yeas later.

While at the Pioneer Press, we shared, with cronies like Katherine Lanpher and Rick Shefchik, long lunches that were basically competitions to see who could say what that would make the others blow coffee out their noses. (Nick, as his closest, dearest friends will tell you, not only kept the most astonishingly cluttered desk, a teetering slum of paper, tchotchkes and long dead paper cups, but was also the world’s messiest diner. His corner of the table at the end of lunch looked like it had been hit by an ISIS mortar attack. A 40% tip couldn’t begin to compensate whoever had to clean up after him.)

As Nick saw it, a metro columnist’s license was like a diploma from the Mike Royko/Jimmy Breslin school of full contact journalism. Far from getting a pass because of their social standing, and the high likelihood they would soon be making cocktail circuit chatter with newspaper bosses, the plump and entitled of the city were irresistible targets for attack, or even a classic Irish feud, as Coleman’s brawls with Garrison Keillor proved.

Moreover, righteous liberal politics were baked into the gig. The fat cats could hire platoons of flacks to spin their saintliness. But the people they were constantly screwing over needed someone with a big public pulpit to argue their case. Nick saw himself as that guy.

Unfortunately as he found out, the game was shifting. The well-fed, glory days of newspapering – where indignant, bull moose-like columnists could lay regular siege to the thin humanitarian veneer of community leaders — were being replaced with an ever more corporatized editorial culture.

Never exactly a hot bed of provocateurs, (other than the sports department), as the internet squeezed their parent companies (i.e. private equity bandits) regional papers like the Star Tribune and Pioneer Press subtly but steadily migrated toward an institutional voice that was less personal and less confrontational and more committed to what we’ll euphemistically call “consensus building”.

Stoking partisan anger with columns attacking the slick cynicism of sitting governors – Coleman v. Pawlenty for example – was, uh, discomfiting to managers charged with sustaining circulation and ad revenue in conservative, outer ring suburbs and maintaining good relations with major, usually Republican business owners.

The key admonition to writers inclined to batter the revenue class was to avoid being “needlessly provocative”. What writers like Nick Coleman weren’t supposed to say out loud to their editors’ faces was that they were such pathetic wimps a “needless provocation” could be as little as saying “shit” when you stepped in it.

Nick knew the old newspaper mule of his youth had gone terminally lame when the Star Tribune, with conservative columnist Katherine Kersten and him exchanging (heavily read) volleys over the 2008 presidential election, issued instructions to both to avoid any further comment on the election until it was over. Because you know, that’s when readers want to argue over politics.

Based entirely on Nick’s telling of the, uh, conversations he had with Star Tribune management over that one, it was clear his Obsequious/Deference Deficiency Disorder had gotten him in hotter water than ever before.

No one doubts Nick could be annoying as all hell, and that’s coming from people like me who didn’t have to supervise him. As far as employee-to-employer subservience went, Nick’s basic message to any editor telling him what to do was: “Look, all you need to know is that I’m damned good at what I do, and thousands of people read this paper because of me. So go find someone else to fuck with.”

Classic old school bosses might have yelled back at him and made perfunctory threats, before in the end conceding (to themselves) that he was right and that passionate characters like “that asshole Coleman” were vital to any relevant, healthy newspaper. But the newer crowd, fresh from six months of the corporate management academy, had a much lower threshold for blowback. A big, blustering bear like Nick was seen as a direct threat to their authority.

He had to be controlled.

Nick and I bonded anew in the mid-aughts as the Star Tribune began dropping the hammer on him.

Just as every crisis is an opportunity, the paper’s financial distress presented managers ideal cover to finally deal with “problem” employees. Officially, nothing could be further from the truth. For the record, it It was all about “right-sizing.” But in reality, any news reporter who failed to see what was happening for what it was was too credulous by half and really needed to find a different line of work.

As the Star Tribune tightened the screws, Nick would call two, sometimes three times a day, reporting on the latest ultimatum, squirrely management-speak verbiage and outright insults … at least as he saw them.

It was painful just to hear it. As I say, Nick was a fiercely proud, intensely competitive guy. Moreover he had substantial bottom line proof, in terms of readership, that his talents and distinctive voice were driving eyeballs to the paper. But as he told it, the paper wanted him to either confine himself to a far more modulated tone, you know, emphasizing “the good things that bind us together” instead of, to quote Nick, “the fucking scumbags looting the public coffers”, or give up the columnist gig completely and move over to some straight reporting beat.

The lame mule would also have had to have been blind not to see what they really wanted. Every option would be a public humiliation for such a proud, high-profile writer. The unspoken message to him was: just to go away.

And so he did.

Frankly, based on all the conversations as the shit was coming down, I was worried for him, and I told him so. The biggest difference between the two of us, besides reporting talent, was Nick’s investment in being a public figure. Loved or hated, it didn’t matter to him. He was in the game. He was a player. But removed from the action entirely? I didn’t like the potent.

He was of course a lot tougher and had a deeper pool of resources than I gave him credit for. (Some of my expressions of concern were a way of signaling that people – especially his enemies — would be watching to see how he handled it all, and not to feed the bastards’ lust for schadenfreude.)

In the months after he left the paper we met several times to kick around ideas that might approximate a return to the public stage.

He had tried a radio gig with ultra-lefty AM 950. It quickly went south when the not exactly progressive owner-operator, who was barely paying him gas money, melted down and handed him a list of edicts designed to muzzle The Full Coleman fury of his act.

The only thing missing from her list was a traumatic castration.

(Nick the proud, unrepentant liberal was so reviled by some commercial broadcasters he was literally forced out of the studio when I had him on as a guest on my show at right-wing KTLK.)

When I got the call telling me about his stroke and imminent death I felt a rush of remorse. I hadn’t had any contact with him in five years. Heading out on a camping trip, I crossed paths with his family and him at a sporting goods store in Grand Marais. The formality of the interaction accentuated an underlying tension. What exactly it was, I’m still not exactly sure.

I recall being annoyed when he showed no enthusiasm for a dual-headed media/politics blog, a kind dual exhaust rant fest. I thought it could be fun. It might even attract some attention and some walking round cash. We both agreed that other than celebrity foo-foo and collegial, transactional reporting, media coverage was a gaping hole in the Twin Cities news menu.

I took his disinterest as a reluctance to co-brand with me. Such are my insecurities. What he really thought, I never knew. But suddenly years had gone by and now he’s dead.

Over the years I was often struck when people who knew I knew Nick would ask, “Why do you like that guy?” (My wife adored him BTW. It was all that pained-poetic Irish crap, I’m certain.)

What I couldn’t understand was what they weren’t seeing in what he wrote, and if they bothered to get to know him, the gracious and informal way he treated most people.

The guy plainly had a big heart and a soul. He cared, truly and deeply about the people and causes he wrote about. The obvious converse of caring is that is he saw no good reason to coddle the other crowd, the goddam soulless stooges and jackals making life more difficult for the decent folks.

Yeah, beers with Nick meant listening to a lot of Nick. It’s true what they say about the Irish, “You can tell ‘em, but you can’t tell ‘em much.” But as a dominating force Nick had the immense benefit of being well-informed, damned funny and sincere about the people and things he cared about.

If the trade-off was learning not to wait for him to ask, “So, what’s up with you?” The whole package, the whole experience all put together was well worth your time.

There’s no shortage of boorish egos polluting the landscape. (Lord, if Nick had a column and free rein in the era of Trump!) But there are far too few of the big ego people who thicken and season the (Irish) stew with talent, conscience and, you gotta love it, the theatrical flourish of genuine righteous anger.

Rest easy, Nick. You’ve served your fellow man well.