Governor Tim Walz and Minnesota DFL state legislators are getting glowing national attention for passing an array of progressive changes in recent months. NBC News recently reported:

Nearly four months into the legislative session, Democrats in the state have already tackled protecting abortion rights, legalizing recreational marijuana and restricting gun access — and they have signaled their plans to take on issues like expanding paid family leave and providing legal refuge to trans youths whose access to gender-affirming and other medical care has been restricted elsewhere.

“When you’re looking at what’s possible with a trifecta, look at Minnesota,” said Daniel Squadron, the executive director of The States Project, a left-leaning group that works to build Democratic majorities in state legislatures.

In fact, the Legislature passed more bills in its first 11 weeks of the current session than in the same time frame of every session since 2010, according to an analysis by The States Project.

To me, the lesson is clear: When voters in gridlocked purple states elect Democrats, Democrats deliver on changes that are popular with a majority of voters. However, Republicans who have blocked these same politics for decades see it differently. They’re crying “overreach.” And crying. And crying. And crying.

What’s “overreach?” Republicans claim “overreach” every time something passes the Legislature that they and their ultra-conservative primary election base oppose. A more reasonable definition is passing something that a majority of all Minnesotans oppose, If DFLers are doing that, it would reasonable to conclude that they have gone beyond the electoral mandate they were given in November 2022.

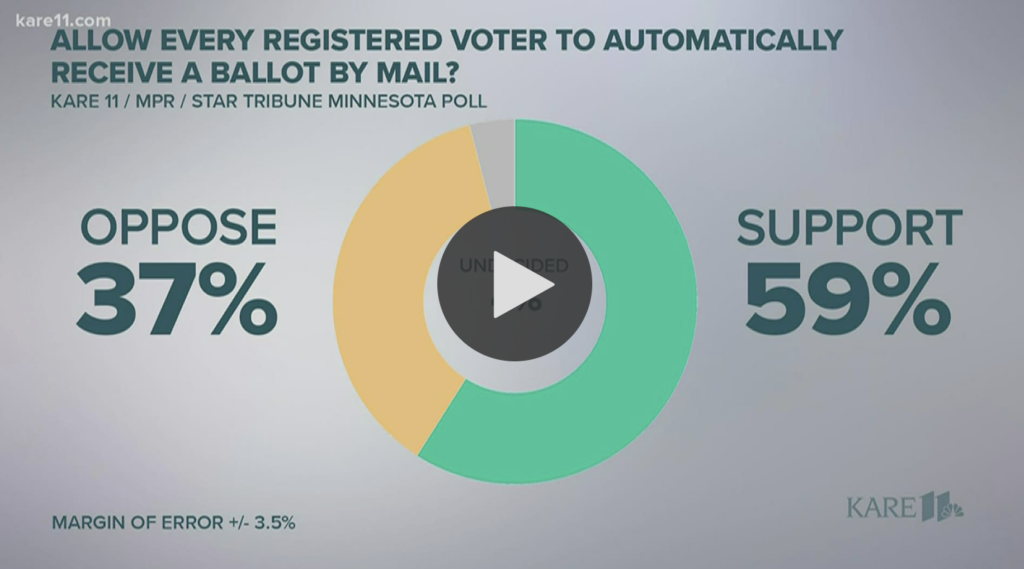

By that definition, DFLers aren’t overreaching. For instance, survey data show that 67% of Minnesotans oppose abortion bans, and therefore presumably support DFL efforts to keep abortion legal in Minnesota in the post-Dobbs decision era. Likewise, gun violence prevention reforms are extremely popular with Minnesotans – 64% back red flag laws and 76% want universal background checks. Sixty percent of Minnesotans support legalizing marijuana for adults. Sixty-two percent support making school lunches free. Fifty-nine percent say everyone should receive a ballot in the mail.

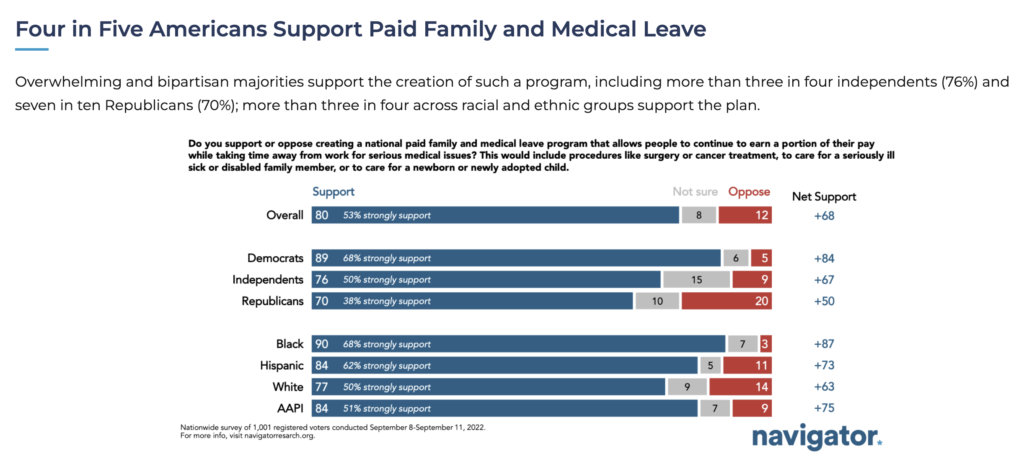

I can’t find Minnesota-specific survey data on all of the other changes DFLers are making, but national polls give us a pretty good clue about where probably Minnesotans stand. Given how overwhelming the size of the majorities found in the following national surveys, there’s no reason to believe that Minnesotans are on the opposite side of these issues: More school funding (69% of Americans support), a public option for health insurance (68% of Americans support), disclosing dark money donors to political campaigns (75% of Americans support), child care assistance for families (80% of Americans support), and paid family and medical leave (80% of Americans support).

Granted, Minnesotans may be a few points different than national respondents on those issues. But it’s just not credible to believe that there isn’t majority support among Minnesotans on those issues.

The only issue where there might be a wee bit of overreach is on the restoration of the vote for felons. While national polls find 69% support for restoring the vote for felons who have completed all of their full sentence requirements, including parole, that support might be a little weaker for restoring the vote before parole is completed, which is what DFLers passed. A survey of Minnesotans conducted by the South Carolina-based Meeting Streets Insights for the conservative Minnesota-based group Center for the American Experiment found only 36% support on this question:

“Currently in Minnesota, convicted felons lose their right to vote until their entire sentence is complete, including prison time and probation. Would you support or oppose restoring the right to vote for convicted felons before they serve their full sentence?”

I don’t suspect that restoration of the vote for felons is a top priority issue for the swing voters who decide close elections. Moreover, the strong 69% support found in surveys for restoring the vote after parole indicates that if DFLers are perceived to be “overreaching,” it likely will be viewed by swing voters as a relatively minor one. Republicans probably will try to characterize this as “a power grab to stuff ballot boxes with votes of convicted criminals” in the 2024 general election campaigns. But they won’t have much luck with that issue, beyond the voters who were already supporting them based on other issues.

I understand that the loyal opposition has to say something as DFLers hold giddy bill-signing celebration after celebration on popular issues. But survey data indicate that Republicans’ “overreach” mantra is, well, overreach.

Meanwhile, to see what actual overreach looks like, see: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/04/opinion/north-carolina-republicans.html?campaign_id=39&emc=edit_ty_20230505&instance_id=91845&nl=opinion-today®i_id=1168208&segment_id=132187&te=1&user_id=9d4d6c1069db85518cc78b30f5087e0e

I suppose the simple comparison is Minnesotans are getting what the majority voted for. Not so in North Carolina.

Yes, the overwhelming majority of North Carolinians want abortion to remain legal and gun violence prevention laws strengthened rather than weakened. But a majority of NC primary voters in heavily gerrymandered districts demand the opposite, so that’s what the majority gets. It’s minority rule, brought to you by the self-described “greatest democracy in the world.”

Felons and voting — a primary problem for people with felony convictions is when they’re able to vote. Making it simpler is better for everyone involved. 1) There ain’t a lot of felons trying to vote. 2) It can be hard to verify whether a felon is eligible to vote on election day. 3) ‘Official channels’ sometimes get it wrong, which creates a gigantic mess, especially, for the felon.

Good points. I agree with the substantive reasons for restoring the vote for parolees. I’m just noting that the surveys indicate that the public may not be as overwhelmingly supportive of that new law as they are with other new laws.