There’s a new book out titled, “Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke and the Making of a Masterpiece.” I pre-ordered it a couple of months ago and when I opened it I came immediately to this quote:

There’s a new book out titled, “Space Odyssey: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke and the Making of a Masterpiece.” I pre-ordered it a couple of months ago and when I opened it I came immediately to this quote:

“Politics and religion are obsolete. The time has come for science and spirituality.”

The story goes that that second sentence was underlined by Kubrick when the quote, from Indian social reformer Vinoba Bhave, was shown to him by Clarke. As a near lifelong (OK, “obsessive”) fan of Kubrick’s work, his emphasis on that line about science enhancing spirituality strikes me as spot on.

It’s been gratifying to see the remarkable outpouring of observance, celebration and reflection on the 50th anniversary of “2001’s” release, April 3, 1968 in Washington D.C. Its gala premiere came amid a historic week. Four days earlier Lyndon Johnson, undone by his prosecution of the war in Vietnam, announced he would not run for reelection. A day later Martin Luther King was assassinated in Memphis.

Very few movies, a generally disposable “art” form, get the attention and respect “2001” is getting these days. Fifty years from now I doubt there’ll be much commotion over the half century anniversary of “The Shape of Water” or even “Black Panther.” That’s because only a handful of large-scale, mass-marketed Hollywood productions qualify as anything close to actual art, with even fewer as willing and determined as “2001” to defy conventional expectations and leave audiences searching their own imagination for resolution.

I was 17 when I saw “2001” for the first time, in late June 1968 at the Cooper Cinerama theater in St. Louis Park. I had been following what I could about Kubrick since being riveted by “Paths of Glory” on TV when I was 14 and “Dr. Strangelove” in a theater a few months later. (“Lolita” required parental permission I did not get.) Here was someone making movies unlike anything else I was seeing in far-off rural Minnesota, a resolutely conventional Mayberry RFD existence where “art” for the most part was something hung on dentists’ office walls.

It took me a few years to accept how profound an effect that first viewing of “2001” had on me. I had driven in to the Cities with my high school English teacher and a couple other pals, and like everyone else in the theater was asking “WTF?” by the time Dave Bowman left his glowing bedroom and floated back to earth as a giant fetus. I remember my English teacher, a fan of “Gone With the Wind”, shaking his head as we filed out and saying, “That was just silly.”

I didn’t know exactly what to say, but the word “silly” was not among anything ricocheting around my squirrely teenage head. All I could process was that anyone who could put that kind of craft and imagery up on a giant movie screen clearly knew what he was doing and more to the point, what he intended to do.

By the time the homicidal, riotous summer of ’68 was over “2001” had separated into distinct partisan camps. Old guard traditionalists remained bored, harrumphing and snorting about “pretentiousness”, as though the only explanation for a movie that didn’t push the normal buttons of escapist entertainment was that it was pretending it was smarter, and on to something they couldn’t grasp.

On the other side, the new guard was reacting like something had just jolted them out of a stupor. Yeah, a lot of the “mind-blowing” was abetted by significant amounts of pot and acid. I must have seen the movie another half-dozen times before ’68 was over, and you knew the repeat viewers by the way they filled the first couple rows of any theater you went to, with some sprawled out on the carpet in front of the front row. (There was the time a pal re-wired the speakers at a drive-in so a dozen of us could, you know, like, commune with the stars while we watched.)

It goes without saying it was that latter crowd — not all on acid — that drove “2001” to legendary status. In it, without always consciously verbalizing it, they were experiencing art. Not just art-ful camera work, or an art-ful musical score, but the art of the overall concept. That being a step up from mere masterly filmmaking craft work to something that invites and requires viewers to allow their imaginations to fire up, reboot and realign as though solving a puzzle.

A constant of Kubrick’s world view, seen most vividly in “2001”, but in some form in all of his films, is that we are not a particularly evolved set of creatures. We live fitfully and irrationally, in a way that is not all that improved from desperately hungry proto-humans clubbing tapirs for food in Africa a couple million years ago. We are still far, far too easily controlled by basic animal impulses and instincts — fear of the other, greed and an emotional subservience to higher authorities — like the corrupt generals in “Paths of Glory”, the sociopathic fools of “Dr. Strangelove”, the police, politicians and scientists in “A Clockwork Orange”, the vain, powdered elites of “Barry Lyndon” and so on.

Politics and religion are obsolete as honest vehicles for delivering us to … something better than this … because the success of each relies on exploiting the most basic and worst of our unevolved emotions and impulses. You only have to acknowledge how much both politics and religion rely on a kind of sanctimonious demonizing of others to see Kubrick’s point.

As Bhave’s quote asserts, the reaction then of rational man to the astonishing revelations and still unfolding mysteries of science — or to explorations of human psychology, biology and the incomprehensible vastness of the universe — is genuinely spiritual. It is a transcendant experience in how it separates us, if only for a few moments, from the chaos and fraudulence of life. Science presents a spirituality qualitatively different from what so many billions still hear from their pulpits, in that it doesn’t rely symbolic fables, highly suspect history and accepting faith as fact. It is transcendence through reality.

As I say, when all that is introduced to your intellectual life stream — via a movie — it is safe to say you’ve been exposed to something truly unique and remarkable.

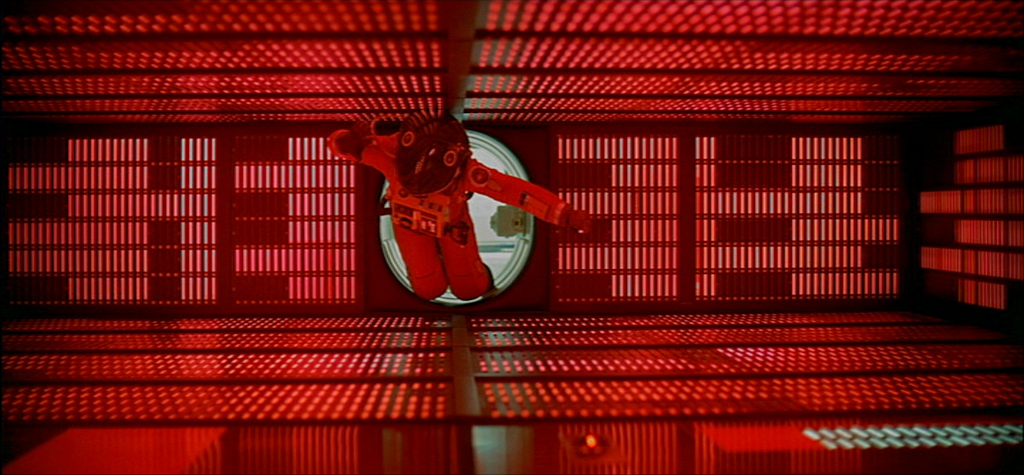

(Stanley Kubrick, in blue jacket, directing “2001”).

(P.S. Christopher Nolan, director of “Dunkirk”, “Inception” and the Batman trilogy, makes no apologies for his indebtedness to Stanley Kubrick for re-orienting his notion of what film — the craft and sequencing of image and sound — can do. He has called “2001” “pure cinema”. He will introduce an “unrestored” 70mm print of “2001” at the Cannes Film Festival next month, simultaneous with a re-release of “2001” around the country in May.)

I’ll be in the front row.

I was 26 when “2001” came out, and I felt I was in the minority among folks I knew when we discussed the film. Your observations fit the experience very well. I read a newspaper review or columnist who made the comparison with the highly popular, cult-inspiring (and just canceled in 1968?) “Star Trek”: “2001” is real science fiction, real imagination of a possible future, while “Star Trek” was a Western set in space. I think that applies to “Star Wars,” too.

Thank you for a great article!

Glad you enjoyed it. The movie is still a marvel to watch and the new book is pretty good, too.