Why can’t the Minnesota Legislature give consumers a MinnesotaCare buy-in option so that they have a guaranteed health insurance coverage option, more doctor choices, and much better price competition? An army of corporate lobbyists say it’s because reimbursements to the health care industry would be lower under that approach, an argument that froze legislators into inaction during the 2019 legislative session.

To be clear, if that argument prevails, Minnesota lawmakers will never contain health care costs.

To contain costs, policymakers have to lower the amount of money going to the major cost drivers — insurance overhead, doctors, nurses, medical devices and pharmaceuticals. If politicians reject a reform every time lobbyists for those cost-drivers object about getting lower reimbursements, they will never contain consumer costs.

Let’s look at one of those cost-drivers, physicians. Politicians like to complain about insurance overhead and pharmaceuticals, for very good reasons, but that’s too easy. Let’s look at the most sacred of health care’s sacred cows. Doctors have an abundance of fans, campaign donating power, and lobbyists, so politicians are especially afraid to direct cost-control efforts at them.

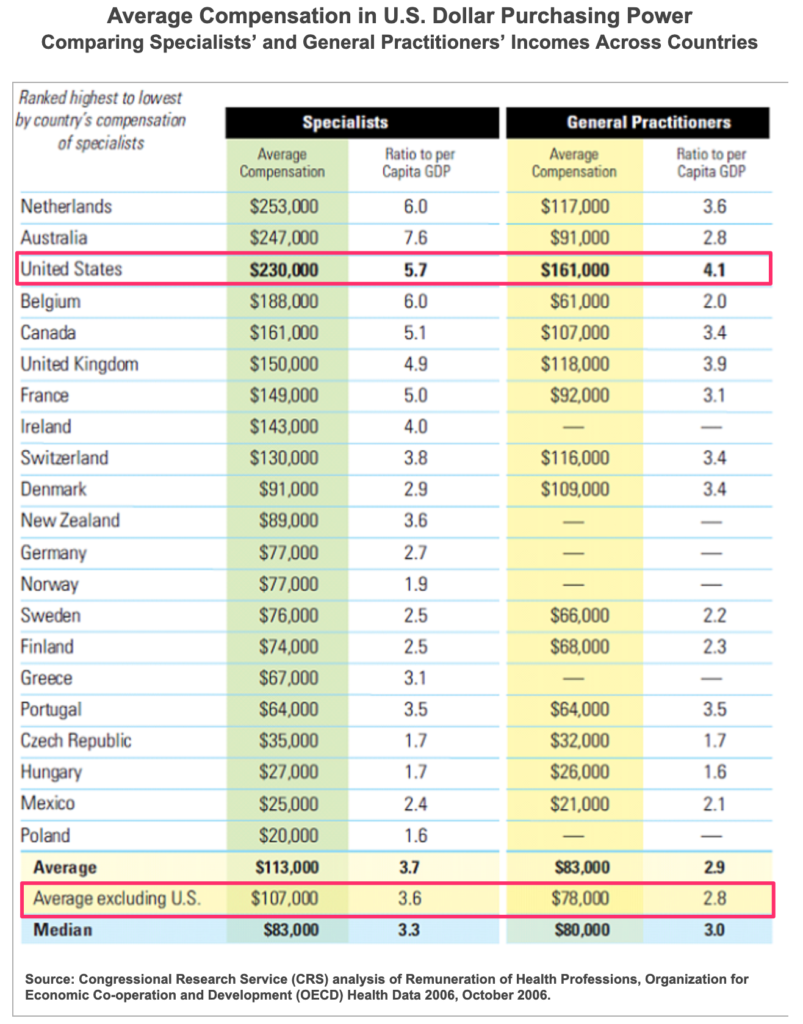

When you look at the long list of developed nations where physicians are paid less than in the U.S., paying less for doctors seems reasonable and doable. For example, the average specialist in the U.S. earns $230,000 per year, while the average specialist in other industrialized nations receives less than half that amount, $107,000 per year.

Remember that the next time you hear physicians and their lobbyists complaining about reimbursements being too low.

Oh and by the way, the health outcomes in those developed countries with modestly paid physicians are better than in the U.S. So don’t buy the claim or inference that better pay automatically leads to better care. It doesn’t.

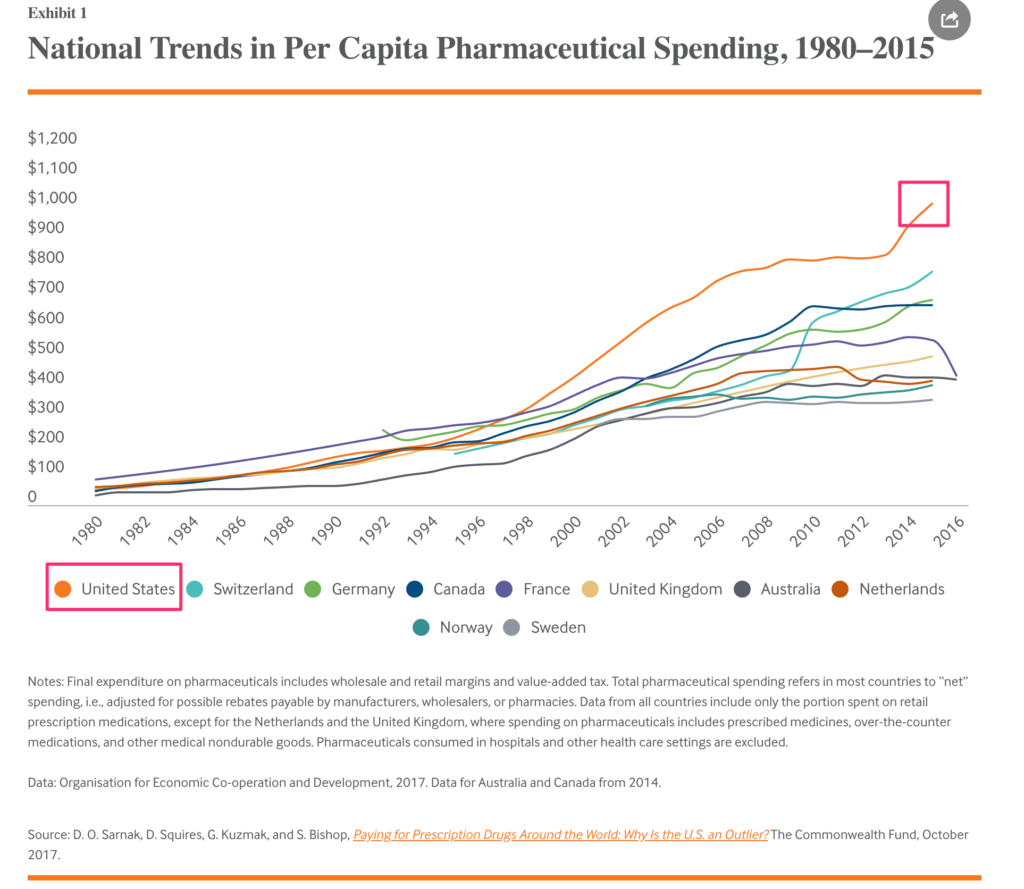

And about those pharmaceuticals. American patients pay much more for pharmaceuticals than patients in many other developed nations around the world. Remember that the next time you hear lobbyists complaining about Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements being too low.

(On this front, the Minnesota Legislature needs to pass legislation to allow importation of Canadian pharmaceuticals, as I argued a while back. Florida recently passed such a bill, but Minnesota politicians remain frozen by health care lobbyists.)

A Minnesota Care buy-in option — branded as “ONECare” in Minnesota by Governor Tim “One Minnesota™” Walz — would ensure that every Minnesotan always has at least one health insurance option available to them, which is particularly important in remote rural areas. It would give them broader networks of caregivers, which again is important to Greater Minnesota residents. It would provide comprehensive benefits and a service that gets good consumer reviews. It would bring better price competition to hold down the health insurance costs. Those all would be huge benefits for hundreds of thousands of Minnesotans.

But not if Minnesota politicians get cowed into inaction every time corporate health care industry lobbyists complain about receiving lower reimbursement rates. If this group of legislators won’t do the right thing on a MinnesotaCare buy-in option, we should elect a new group who will.

Great column. Over prescription of over priced drugs is a huge issue. Additionally, our for profit healthcare model has no incentive to control cost. In fact they get rewarded by the stock market for revenue growth and price increases.

Couldn’t agree more, Joe. I used to work for a hospital and clinic business, and almost uniformly met really compassionate and well-meaning folks. I’m not trying to make villains out of them. These are not bad people. They’re just regular people responding to bad market incentives. Where profit-making incentives are the problem, the incentives have to be changed.

For private goods, a reasonably regulated free market makes sense. But for public goods like health care (and if you believe healthcare is a right, it’s a public good), the free market is simply the wrong model. We have to ultimately get to a single payer system like every other sane, developed nation in the world, but a public buy-in option is a politically doable bridge to that ultimate goal. https://www.wrywingpolitics.com/medicare-buy-option-next-span-bridge-medicare/

Cost and expense of attending medical school needs to be addressed as well. Of course high paying jobs draw people to the profession and the expense of the education means high paying jobs are required to pay off education debt. At least this is my unsupported thought about the matter.

I guess I would say this: 1) doctors in other countries who are making less go to med school too; 2) if other nations are subsidizing medical school educations to keep doctor’s debt down, maybe we should too, particularly if they agree to provide care in underserved areas or go into primary care where the public need is greatest.

I am in general support of your article. However, the cost of education for medical professionals in the U.S. needs to be taken into account as well. My understanding is the average student debt load for this group is extremely high. So as we contemplate lowering physician pay, we also need to couple that with lower education costs so we don’t discourage entry into this field altogether.

You make a fair point, Noel. Worth putting in the equation. See my comments to Cameron above.

Beyond what I said earlier, let me add this: Show me a doctor who is both paying loans and struggling to make ends meet and I’d have more sympathy.

All around me, I see docs, particularly specialists, who are paying loans while still living in relative luxury. The loan payment isn’t precluding the huge second homes and Range Rovers. Therefore, I’m not convinced the student loan burden for doctors is nearly as severe as it is for social workers, teachers, nurses, etc.

Still, I’m sure willing to look at ways to relieve that burden as we ask them to take salaries more in keeping with the rest of the world’s physicians.

I live in Duluth, and I am married to a physician. When we first moved here in 1994 (from St. Paul), the physicians’ parking lot was filled with Dodges, Chevies, Saturns, etc. Now my husband says the lot is filled with Porsches, Audis, BMWs and other high end luxury cars. And instead of living in ranch homes or older houses a lot of physicians are living in huge new luxury homes.

Physician salaries have gone up here and across the U.S. Part of it is that there are fewer doctors as a proportion of the population, so the rule of supply and demand kicks in. In rural areas (like that served by Duluth) it’s more difficult to recruit physicians. Doctors here don’t get paid more than the industry standard, but salaries do have to fall well within the the standard range, whereas in desireable locations (like just about anywhere on the West Coast) the salaries can fall in the lower range of the standard.

We have many physicians in town who only have to work part-time to earn a very good living. Thus residency programs are graduating people who are contributing 1/2 as much labor as they would as full-time physicians. The economics of that are not good, since medical schools are expensive to run and depend on government subsidies (paid for by us all), and there are a limited number of slots to train future doctors. I don’t know if the move toward more part-time work is contributing to the physician shortage to any great extent, but it certainly can’t be helping.

So yes, physician salaries are one cause of cost increases. However, another contributing factor — a huge one which is hardly ever discussed — is the fact that research driven innovations constantly create new devices, drugs, and treatments that seem to be getting more and more expensive. Many of them cure diseases that only a small percent of the population suffers from, but the costs of which everyone must bear. And many expensive new drugs are only a little more efficacious than the older drugs they’re replacing. Some of the newer innovations are indeed cost efficient, but the question of cost efficiency does not seem to be taken into consideration when deciding whether or not to incorporate them into treatment plans.

At some point we may need to ask ourselves how much innovation we can sustain. If we had stopped all medical research back in the eighties and were still using the same technologies and drugs we had back then, we’d be doing well enough (which we were in the 80s), and paying a lot less. The ethical question of how many increasingly expensive innovations we can or should afford is huge, but it would be good if we at least started talking about it.

Extremely good and important point about the role extremely expensive incremental medical “improvements” have on patients’ costs and, ultimately, patients’ access to care. Thanks for that, Ruth.

This classic 3-minute Monte Python sketch about The Machine That Goes Ping makes that point brilliantly — https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=arCITMfxvEc

On physician salaries, I certainly don’t mean to imply that physician salaries are the biggest cause of medical inflation, or that physicians should have to take an oath of poverty. Physicians are highly trained and valued professionals and should be reimbursed well. Mostly, I just brought physician salaries up, because lawmakers are afraid to even talk about that issue, preferring easier targets like Big Pharma and corporate insurance companies. I’m just saying that data about physician salaries from around the world suggests that limiting public health plan reimbursements for physicians is not something policymakers should take off the table. It’s far from the whole solution to medical cost containment, but it’s one part of the solution.

Yes, I remember the machine that goes Ping! Thank you for that.

I have no idea what physicians should be paid. My husband says that primary care physician salaries have gone up significantly faster than inflation over the last 20 years (salaries have about tripled), and he believes they have gone up too much, allowing a level of conspicuous consumption not seen in the past among primary care docs. The salaries have greatly increased for specialists too.

He believes that physician salaries in general contribute to the healthcare cost crisis somewhere between 5 and 10%. That’s a seat of the pants calculation.

I’m no expert, but that percentage for docs seems about right to me too. I spotlighted it mostly because it’s maybe the least politically acceptable for politicians to go after, which bugs me. But without a doubt, there is more savings to be found in the overhead, pharmaceutical, over-use, and device categories.