I recently wrote to Minnesota legislators to ask them to end marijuana prohibition, as many states have recently done. The responses I’ve received have been disappointing, not because they disagreed with me, but because they were utterly vacuous.

I recently wrote to Minnesota legislators to ask them to end marijuana prohibition, as many states have recently done. The responses I’ve received have been disappointing, not because they disagreed with me, but because they were utterly vacuous.

In matters of political debate, I’m a big boy. For more than thirty years, I have worked in and around bare knuckle politics. I grew up a liberal in a deep red state (South Dakota), so I am very accustomed to losing arguments. Still I value a good substantive discussion, because that’s how attitudes change over time.

But what I got back from Minnesota legislators was birdbrained political handicapping, not substance. I sent them a note with this evidence-heavy blog post, and expected at least a somewhat substantive rebuttal to my arguments.

Instead, I got responses like this from Minnesota legislators (excerpted):

“…it is highly unlikely in the foreseeable future that the Minnesota Legislature will take such a step.

…

Numerous concerns have been expressed about the negative impact legalization would have on public safety, and the incidence of addiction.

…

Nonetheless, please know should any proposals related to marijuana come before me, I will give them the thoughtful consideration they merit.”

Blah, blah, blah. I don’t use marijuana, but reading these responses made me dumber than any drug ever could. Every response I received had a similar cavalier shrug of the shoulder, political handicapping, “some people say…” passive aggressiveness, and refusal to state a personal position or respectfully rebut mine.

In my misspent youth, I spent a few years drafting such responses for a U.S. Senator. So I’m a bit of a connoisseur of this dark art. My liberal former boss always insisted on providing his mostly conservative constituents with his evidence-based arguments. He felt he owed them that, that it was a sign of respect. I got nothing of the kind from Minnesota legislators.

Obviously, the chances of overturning marijuana prohibition under a GOP-controlled Legislature, U.S. Department of Justice, Congress and White House are nonexistent. But I took the time to contact legislators because I wanted to educate them, compare notes and move the conversation forward. I know that popular opinion on this issue is changing rapidly, and that election swings change political calculations overnight, as we saw with marriage equality. So I sincerely wanted to gain a better understanding of how Minnesota legislators were processing the issue.

If Minnesota legislators really believe that marijuana is more addictive than alcohol, show me your data. If they really believe that marijuana laws aren’t being used to disproportionately punish people of color, show me your data. If they really believe that marijuana kills more people than alcohol, or causes more health problems, show me your data.

And if you concede the accuracy of all of the data that I’ve supplied, explain the logic of continuing prohibition of marijuana, while expanding the availability of much more destructive alcohol products.

That type of disagreement I can respect. That kind of disagreement moves the democratic dialogue forward. But using “it’s not going to pass” and “some interest groups say…” deflections as a substitute for substantive debate is for pundits, not policymakers.

Joe, the legislators have spent decades imbibing reefer madness, both the total propaganda package and the “conventional-political-wisdom-says-steer-clear-of-it” sub-set. But it’s not just Minnesota. Not a single state legislature has yet enacted a repeal of prohibition against the personal use of cannabis by adults for non-therapeutic circumstances. How have seven states (and DC) begun to dismantle prohibition? By popular vote, using the ballot initiative petition process. We can’t do that due to our Minnesota state constitution, and that’s the obstacle to progress here.

Nevertheless, several lawmakers have finally broken the taboo and proposed a fairly timid version of a personal-use legalization bill. A handful of DFL-ers led by Metsa and some other Iron Rangers, along with Applebaum from Minnetonka, proposed that the issue be framed as a Constitutional amendment. Thus the legislature could leave the decision up to a vote by the people, without having to “take the risk” of themselves being seen to vote for repeal.

What is that “risk”? It isn’t popular disapproval–because it’s by popular vote that legalization has passed in those other states, and it’s at least an even bet to pass here if we had a chance to vote. No, the risk is the retaliation that politicians fear from the vested interests which profit from prohibition. These include police union lobbyists, county attorneys and prosecutors, the liquor lobby, the drug-addiction-treatment lobby (very potent in MN), pharmaceutical companies, professional minders of other peoples’ morals such as Minnesota Family Council, private prison promoters, and other profiteers.

Each legislator receives a continual stream of e-mails and other input from the prohibition interests, notably the “Smart Against Marijuana” outfit run by Kevin Sabet. They provide ready-to-hand anti-legalization talking points. That’s where the “some people say” originates.

If progress towards a rational reform is to happen, it will require organization beyond just lobbying and writing to members (although that part of the process is what I’ve been pursuing since the 1970’s, along with every other type of advocacy that I can attempt.) I appreciate your determination to offer evidence–but that’s precisely what HASN’T driven drug-related politics, through these long and dreary decades of fear and loathing.

Years ago, we studied the history of repealing alcohol prohibition. The decisive factor wasn’t all the socially-destructive side-effects of prohibition (crime, corruption, violence, adulteration, infringement of liberty, disrespect for all laws, etc.) It was the need for revenue which propelled repeal in 1933. And when the tide turned on that issue, it turned with amazing speed. Perhaps the fact that so many politicians and newsmen were hard drinkers themselves made it easier to reverse the error of alcohol prohibition–a situation that isn’t replicated with cannabis, unfortunately.

Still, I’m encouraged that even in the political climate you so accurately described in your post, of indifference, cowardice, ignorance, and timidity, there are now cracks in the edifice of prohibition. By now, a dozen representatives have signed onto HF 926–a hefty handful of straws in the wind! Besides the “young Turks” who brought in the first legalization bills, a couple of veteran legislators have also been quietly working on a similar proposal that may represent a more comprehensive and consumer-oriented model. Ending cannabis prohibition is one issue of public policy where the people are way ahead of the politicians. That means that the politicians who do seize this issue are going to become popular heroes while their more cowardly colleagues will have to scramble to get on board later.

Please note: the 2016 DFL state convention adopted an Action Agenda plank supporting the legalization of both medicinal and “recreational” (personal use) cannabis. Politicians routinely disregard the party platform–at least, DFL politicians do–but in this case, it behooves them to listen to their own rank and file supporters.

Thanks for the update, and for continually being out there making the case.

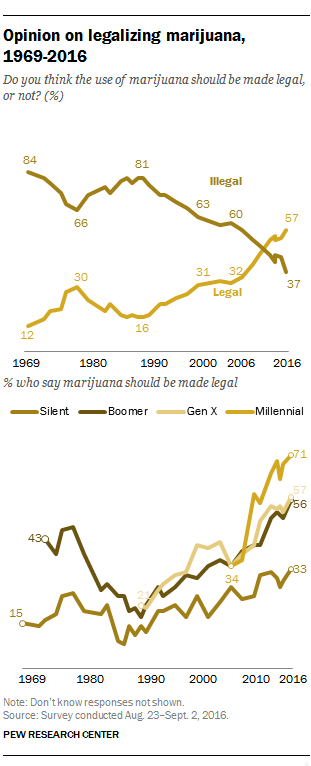

The timidity of the police-fearing elected officials is discouraging, but those surveys are what give me hope. Politics can change surprising quickly when public opinion changes fast. As you look at those generational differences, public opinion is going to be changing quickly in coming years.

The fact that legislators won’t engage in the substantive arguments leads me to believe that they know marijuana prohibition makes no logical sense. Political power, not logic, is biggest barrier, and public opinion will eventually cause them to reassess the politics of the issue.

I can’t quite generate the juice to grab up pitchfork and torch for retail pot. But I think of it like Sunday liquor. As in: Let’s move on here. Sheriff Stanek I think is an outlier among cops in his passion for pot “enforcement”. How many other cops actually want to bother with it? What are the current numbers in terms of time lost (to paper work if not prosecution) in enforcing current prohibitions? Beyond that of course — and this is always a personal favorite — how many of these timorous law and order types have or are engaging in recreational pot use themselves (or have alcohol problems?) Then … who is it exactly they fear? What is the face and size of the crowd ferociously opposed to pot reform that it is a vote-the-bastards-out issue?

Legalized pot is more than just a nice-to-have amenity, like Sunday liquor sales. Enforcing marijuana laws is crazy expensive and it needlessly fucks up the lives of a lot of young people. It wreaks a lot of societal havoc.

https://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/29/opinion/high-time-the-injustice-of-marijuana-arrests.html?_r=0

Lawmakers are typically politicians first and “statesmen” (or -women) second; their re-election is their main concern. Ninety years of reefer madness have conditioned them to reflexively support every “anti-drug” proposal and to reject pleas for reform.

The “drug war” came in handy as a demagogic device for our domestic fascisti after the end of the Cold War. Liberals who could no longer be smeared as “soft on communism” because communism seemed irrelevant could instead be smeared as “soft on crime” or “soft on drugs.” And as was understood by Nixon, Reagan, Bush and by their political strategists, “war on crime/drugs” could very successfully serve as the conduit for the kind of racial antagonisms which they exploited in order to appeal to the George Wallace voters—insecure white working class folks who used to be Democrats. The response of Clinton-style Democrats was to outshout the Republicans and double down on mass incarceration and more police state gimmicks like asset forfeiture and militarized enforcement.

So they have a lot of unlearning to do. The task is made harder because so few citizens are willing to speak openly against prohibition. That almost palpable fear to speak openly is an index of how profoundly the narco-police state has affected our society. The issue is not about “pot” (an obsolete slang word nowadays) but about prohibition.