I adore my home state of South Dakota, but I rarely find myself calling for my adopted state of Minnesota to copy South Dakota policies. On a whole range of issues from progressive state income taxes to a higher minimum wage to LGBT rights to dedicated conservation spending to teacher pay to Medicare coverage, I wish the Rushmore state’s policies would become more like Minnesota’s, not vice versa.

But if a majority of South Dakota voters embrace Amendment T at the polls this November, I may soon be feeling some serious SoDak envy.

Once every ten years, all states redraw state and congressional legislative district lines, so that the new boundaries reflect population changes that have occurred in the prior decade. In both Minnesota and South Dakota, elected state legislators draw those district map lines, and the decision-making is dominated by leaders of the party or parties in power.

Once every ten years, all states redraw state and congressional legislative district lines, so that the new boundaries reflect population changes that have occurred in the prior decade. In both Minnesota and South Dakota, elected state legislators draw those district map lines, and the decision-making is dominated by leaders of the party or parties in power.

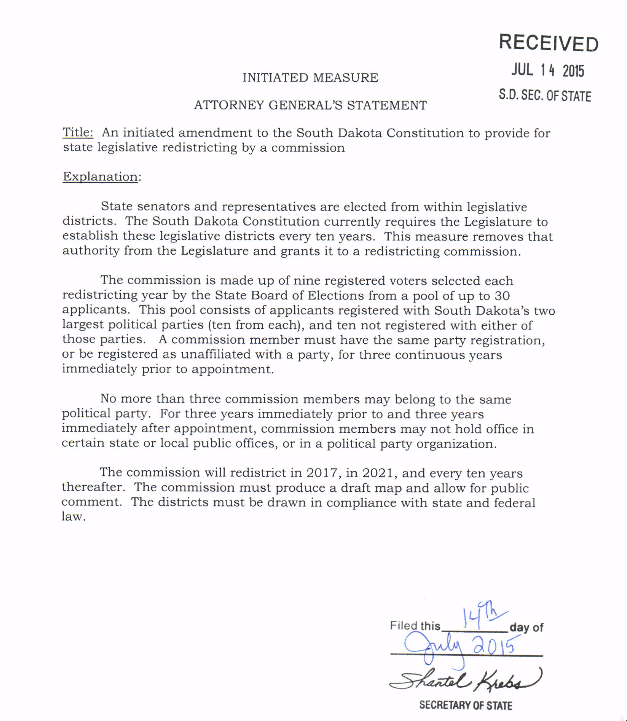

South Dakota’s pending Amendment T calls for a very different approach. If a majority of South Dakota voters support Amendment T this fall, redrawing of legislative district lines would be done by a multi-partisan commission made up of three Republicans, three Democrats and three independents. None of the nine commission members could be elected officials.

The basic rationale behind Amendment T is this: Elected officials have a direct stake in how those district boundaries are drawn, so giving them the power to draw the maps can easily lead to either the perception or reality of self-serving shenanigans.

The basic rationale behind Amendment T is this: Elected officials have a direct stake in how those district boundaries are drawn, so giving them the power to draw the maps can easily lead to either the perception or reality of self-serving shenanigans.

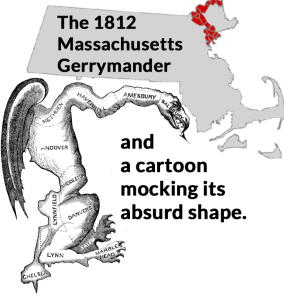

As we all know, redistricting shenanigans are common. Guided by increasingly high tech tools and lowbrow ethics, elected officials regularly produce contorted district maps that draw snickers and gasps from citizens. Often, the judicial branch needs to intervene in an attempt to restore partisan or racial fairness to the maps that the politicians’ produce.

Gerrymandering and Polarization

There are all kinds of problems created by the elected officials’ self-serving gerrymandering. Legislators in control of the process draw lines to ensure that the gerrymanderer’s party has a majority in as many districts as possible. This leads to many “safe districts,” where one party dominates. In safe districts, the primary election is effectively the only election that matters. General elections become meaningless, because the winner of the primary elections routinely cruises to an easy victory.

In this way, disproportionately partisan primary voters, who some times make up as little as 5 percent of the overall electorate, effectively become kingmakers who decide who serves in legislative bodies. Meanwhile, minority party and independent voters effectively have almost no say in the choice of lawmakers, even though they usually combine to make up more than 50% of the electorate.

In other words, gerrymandering has given America government of, for and by 5 percent of the people.

Because these primary election kingmakers tend to be from the far ends of the ideological spectrum, gerrymandering has contributed to the polarization of our politics. It has created an environment in which elected officials live in fear that they will be punished in primary elections if they dare to compromise with the other party. As a result, bipartisan compromise has become increasingly extinct in many legislative bodies.

Gerrymandering and Distrust

Beyond political polarization, perhaps the worst thing about politician-driven redistricting is that it makes citizens cynical about their democracy. Whether you believe problems are real or merely perceived, the fact that elected officials are at the center of redistricting controversies creates deep citizen-leader distrust. When citizens become convinced that elections are being rigged by elected officials so that the politicians can preserve their personal power, citizens lose faith and pride in their representative democracy. When we lose that, we lose our American heart and soul.

So Minnesota, let’s commit to creating — either via a new state law or by referring a constitutional amendment to voters –our own multi-partisan redistricting commission that removes elected officials from the process. Let’s govern more like South Dakota!

Did I really just say that?

I have not understood why computers do not do the redistricting. Put in the parameters (x voters per district and basic outline to determine where lines are) and let them make an unbiased map. Of course there will be “tweeks” needed (maybe everyone on the block should be in the same district or not divide a house in half) but limit the kinds and amounts of changes that can be done.

With this system no one party should have an advantage, candidates run on their merit, and the district voters decide.